Textile Arts: Spinning

Help for including textile arts and sensory details in your writing

Without spinning, there would be no yarn for making clothing, sails, bed linens, decorative tapestries, tents, tablecloths, napkins, towels, nets for fishing, or pennants for battle. All of those things required hours and hours of work to prepare the fibers and spin the yarn. Then more hours were required to turn it into the textiles needed.

Textiles used to be treasured items before the modern idea of cheap, fast fashion. I find it ironic how little we think of the effort that goes into our clothing today. When I started spinning in the late 1990s, I was excited to create my own yarn and have control over its properties.

Without further ado, I’d like to introduce you to one a textile arts staple, spinning. I’m only able to give an overview today, but I’ll share a page of resources at the end so you can dig in deeper.

What is Spinning?

To create yarn, you add twist to a set of fibers. The twist holds the fibers together. Before the twist enters the fibers, you pull the them apart and only allow the amount of fibers you want in the yarn. This is how you control how thick or thin your yarn becomes.

What Keeps It From Unraveling?

There are a few ways to keep the fibers from untwisting and falling apart. The first is plying yarn. It’s where you use multiple lengths of yarn—called plies, and twist them so they spiral around each other—much like candy cane stripes.

Another way is setting the twist by steaming or felting. This is useful for single ply yarn. Though if you steam yarn, you may need to be repeat it if the yarn or created item is washed.

Felting is permanent. If the fibers felt, they catch on each other and interlock. Plant fibers and silk don’t felt. Most animal fibers (wool, llama, rabbit, etc.) are hair, and interlock when heat, motion, and water are applied.

Main Spinning Tools

Spinning yarn is done either on a spindle or a wheel. I’ve included a demonstration video (in the resources) that I made a few years ago. It shows both spindle and wheel spinning. Spindle is the first part. The wheel section starts at about 44 minutes into the video.

Drop Spindles

Spindles come in many shapes and sizes. I’ve included a shop link so you can see different types. Spindles are the oldest tools for spinning yarn.

They often have a weight, called a whorl, which can be anything from a rock or potato to an intricately carved disc or a set of crossed arms.

The whorl is near the top or bottom of the shaft, compared to where the yarn connects to the spindle.

Usually, fiber is attached to a leader yarn on the spindle. Then the spinner starts the spindle spinning and drops the spindle to spin freely. (I dare you to say that 5 times fast!) The spinner next drafts the fiber (pulls some fibers out of a group) and lets the twist enter that new set of fibers, creating a new section of yarn.

They repeat this until the spindle almost touches the ground or slows too much. When there is sufficient twist in the yarn, the spinner will wind the new yarn onto the shaft of the spindle and they start the process over again.

Supported Spindles

Spindles for very fine yarns, such as those for lace, are often supported. The spinner lets them spin on a surface or in a bowl. Single ply yarns for Navajo weaving are spun on a large support spindle. The tip rests on the ground and the shaft of the spindle is rolled on the spinner’s thigh.

Wheels

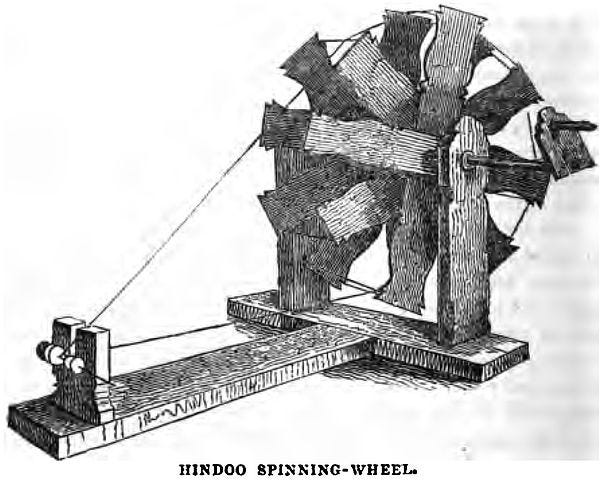

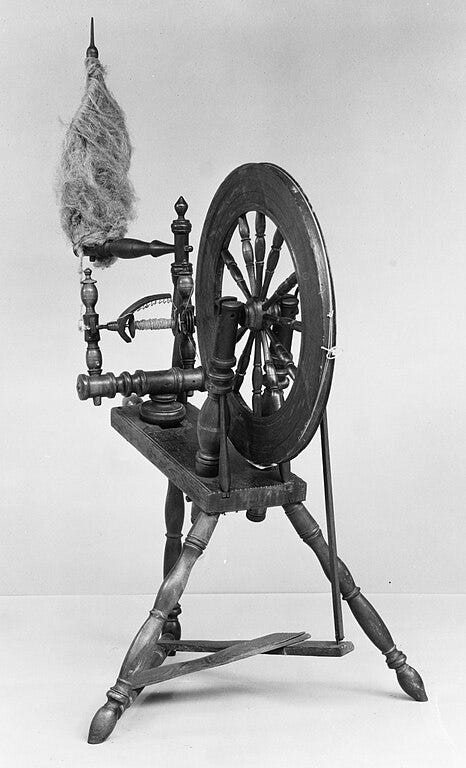

We often think of a spinning wheel when we think of making yarn. The oldest wheel styles I have seen are spindle wheels—such as walking/great wheels or chakra style. Regions often have specific historic styles.

There are many types of spinning wheels, I won’t get into detail on them because this article is only an overview. But I will share a few pictures and an article on different types.

Here are a few historic wheels.

And to contrast, here are a few modern wheels.

As with spindles, the idea is to twist fibers so they stay together as a continuous strand of yarn. The wheel may have a foot pedal, crank, or rely on the spinner to hand turn the wheel. It provides the twist and the new yarn is collected up onto a bobbin or a spindle.

Wheels with bobbins use tension to help pull the thread onto the bobbin. The article link above (about different wheel types) goes into the different types of drives for wheels and how tension is created. With a spindle wheel, your hand holding the completed yarn provides the tension.

Types Fibers

Historically, two types of fibers were available: plant and protein fibers. The most common plant fibers are cotton and linen. Protein fibers are most often from the hair of an animal or the silk from a moth’s cocoon.

Wool is the most well-known animal fiber. Generally, the finer the fiber diameter, the softer the wool is. Sheep are often raised for meat or wool. Though there are breeds that can be used for both.

I’ve had questions about animal cruelty when I spin at demonstrations. So, I’ll cover it quickly. The animals get a haircut, get brushed, or molt when the fiber is collected. A good shearer won’t cut or nick the animals. Sheep, llamas, alpacas, angora goats, yaks, camels, etc. grow their coats out again. Angora rabbits may be sheared or their coat may be plucked.

I only know of one animal fur fiber for spinning where the animal is killed—but not for the fur—which is a by product. It’s fox fiber, and it’s hard to find and I won’t spin it. (Note, it shouldn’t be confused with Foxfibre natural colored cotton, grown by Sally Fox. If you Google fox fiber, you see her lovely cottons.)

Silk is an exception to this. The silk moth caterpillars usually stay in their cocoons as the silk is processed (by cooking) so it can be reeled off. They don’t survive. If they hatch first, the single silk strand they had spun is broken. That said, there are cruelty free silks. Several of these are wild silks like Tussah.

Just because it’s too fun not to share, I’ll mention a group created a spider silk cape. After the spiders finished spinning, the group released them. It took over a million spiders to spin enough silk threads.

Pet fiber, such as dog and cat fur, can be used, though it’s not common.

Manufactured fibers are popping up for spinning, including: soy silk, bamboo, corn (called Ingeo), viscose, tencel, and milk fibers, just to name a few.

Spinning for the Senses

I’ve been anxiously waiting to share this section with you! Once you learn spinning, it can be an incredibly relaxing craft as you repeat the same motions over and over in a rhythm. There are so many possibilities for the senses, too! So, I’ll share a few lists of things to consider for your writing.

Feel and Sight:

Texture of the fibers: Are they rough or soft? Depending on the fiber it could be very soft and fluffy—like merino wool or angora rabbit fur. Soft yarns are chosen for garments next to the skin. More toothy (less soft) ones aren’t as fragile. Fibers can be coarse, like wool for rugs. They can be smooth like linen or rough like jute for ropes.

Does it stick to your hands? Silk catches on any dry spot on my hands. Wool that hasn’t had all the lanolin washed out can be a little tacky to the touch when spinning. The lanolin can act as a water repellant.

How fine or thick is the yarn? Yarn for lace will be almost like thread. Yarn for mittens and sweaters is thicker.

How long has the spinner been doing the craft continuously? Their hands and wrists may hurt and cramp, depending on what spinning style they're doing. Other styles are easier on the hands.

How hard is it to process the fiber? Wool combing and hand carding can be hard on the hands and wrists.

What is the texture of the yarn? Are there bumps or is it smooth? Boucle is an example of a fancy bumpy yarn. Are there things added into the yarn, such as fiber clumps, other yarn, beads, feathers, etc?

What is the yarn made of? Cotton is often thicker and heavier than wool. Wool can be super soft (Merino) or scratchy (carpet wools). Alpaca is silky with lots of drape. Llama is a lot like sheep wool. Milk protein fiber shines like silk. And linen is cool to the touch and has a nice sheen.

Smell:

Depending on the time period and purpose, you may have lanolin (which is often found in lotion) remaining in the yarn. It's great for weather proofing. Think Irish fishermen’s sweaters.

The type of fiber in the yarn can affect the scent. If the spinner mixes dog hair and wool, when the yarn is wet there will be a dog smell. (I had an acquaintance who would spin wool and dog hair to make rugs so she could remember her dogs after they passed away.)

Dyes, if they aren’t used up and there’s still some in the yarn can affect the smell. Also dyes when dyeing have distinctive smells. Urine was an ingredient in many historic dyes. It helped the fabric stay wet and concentrated the dye in the vat. In modern dyeing, we can use chemically made urea, instead.

Sound:

Spindles are pretty quiet unless they drop. You may hear a flicking sound as the spinner starts the spindle spinning.

Wheels have a whir. Sometimes they have a squeak (if the treadle or pedals need oil), and other time a rattle or repetitive click.

Resources

Hopefully, this post gave you a ‘taste’ for spinning. If you’d like to learn more or see videos of spinning being done, I have a resources page that I’ll update for each craft I share about. (This post was getting too long for email, and gathering the resources in a separate post allowed me to share more today!)

That’s what I have on spinning basics. Though, there’s more to come! In future posts, I’ll share about preparing fibers for spinning, plying yarn you’ve spun, knitting, nalbinding (a yarn craft much older than knitting or crochet), and more!

Do you have questions about spinning? Let me know in the comments and I’ll do my best to answer.

If by chance, textile arts are not of interest, you can subscribe to sections of my newsletter separately. (Here’s the Substack help page on how to do that.)

Remember to…

Be the Difference. Be extraordinary.

All the best,

Amy